|

Darwin, C. R. Notebook B: [Transmutation of species (1837-1838)].

NOTE:

This 17 x 9.7 cm notebook is bound in brown leather with the border

blind embossed: the brass clasp is intact. Both covers of the notebook

have labels of cream-coloured paper with 'B' written in ink. It

comprises 280 pages inside the covers, all numbered consecutively by

Darwin. Twenty-seven pages were excised by Darwin, of which

twenty-three have subsequently been found. Darwin's reversed question

marks have been transcribed as inverted question marks.

This book was commenced about July, 1837. Page 235 [of 280] was written in January 1838. Probably ended in beginning of February.

[page] 11

. . . In cases as Galapagos and Juan Fernandez

when continent of Pacific existed, might have been monsoons, when they ceased, importation ceased, &

[page] 12

changes commenced

or intermediate land existed, — or they may represent some large country long separated. —

On this idea of propagation of species we can see why a form peculiar to continents, all bred in from one parent

why Myothera several

[page] 13

species in S. America

why 2 of ostriches in S. America. —

This is answer to Decandoelle (his argument applies only to hybridity),

— genera being usually peculiar to same country,

different genera, different countries.

[page] 14

Propagation explains why modern animals same type as extinct which is law almost proved. —

We can see why structure is common is common [sic] in certain countries

when we can hardly believe necessary, but if it was necessary to one

forefather, the result would be as it is. — Hence Antelopes at C. of

Good Hope, —

[page] 15

Marsupials at Australia. —

Will this apply to whole organic kingdom when our planet first cooled. —

Countries longest separated greatest differences — if separated from

immens ages possibly two distinct type, but each having its

representatives — as in Australia.

This presupposes time when no Mammalia existed; Australian Mamm. were

produced from propagation from different set, as the rest of the

world.] —

[page] 16

This view supposes that in course of ages, & therefore changes

every animal has tendency to change. —

This difficult to prove

cats, &c., from Egypt.

no answer because time short & no great change has happened.

I look at two ostriches as strong argument of possibility of such

[page] 17

change, as we see them in space, so might they in time.

As I have before said, isolate species, & give them even less change

especially with some change, probably change vary quicker.

Unknown causes of change. Volcanic isld? —

Electricity.

[page] 18

Each species changes.

does it progress?

Man gains ideas.

the simplest cannot help — becoming more complicated; & if we look to first origin there must be progress.

If we suppose monads are constantly formed, ¿ would they not be pretty similar over whole world under

[page] 19

similar climates & as far as world has been uniform at former epoch].

How is this Ehrenberg?

every successive animal is branching upwards,

different types of organization improving as Owen says,

simplest coming in and most perfect and others occasionally dying out; for instance, secondary terebratula may

[page] 20

have propagated recent terebratula, but Megatherium nothing.

We may look at Megatherium, armadillos & sloths as all offsprings of some still older type

some of the branches dying out.-

With this tendency to change (& to multiplication when isolated requires deaths of species to keep numbers

[page] 21

of forms equable]

but is there any reason for supposing numbers of forms equable? — this

being due to subdivisions and amount of differences, so forms would be

about equally numerous

Changes not result of will of animal, but law of adaptation as much as acid and alkali.

Organized beings represent a tree irregularly branched

some branches far more branched — Hence Genera. —]

As many terminal buds dying as new ones generated

[page] 22

There is nothing stranger in death of species than individuals

If we suppose monad definite existence, as we may suppose in this case,

their creation being dependent on definite laws, then those which have

changed most owing to the accident of positions must in each state of

existence have shortest

[page] 23

life. Hence shortness of life of Mammalia.

Would there not be a triple branching in the tree of life owing to three elements

air, land & water, & the endeavour of each one typical class to extend his domain into the other domains, and subdivision three more, double arrangement. —

[page] 24

if each main stem of the tree is adapted for these three elements, there will be certainly points of affinity in each branch

A species as soon as once formed by separation or change in part of country repugnance to intermarriage increases it settles it

[page] 25

¿ We need not think that fish & penguins really pass into each other. —

The tree of life should perhaps be called the coral of life, base of

branches dead; so that passages cannot be seen. — this again offers

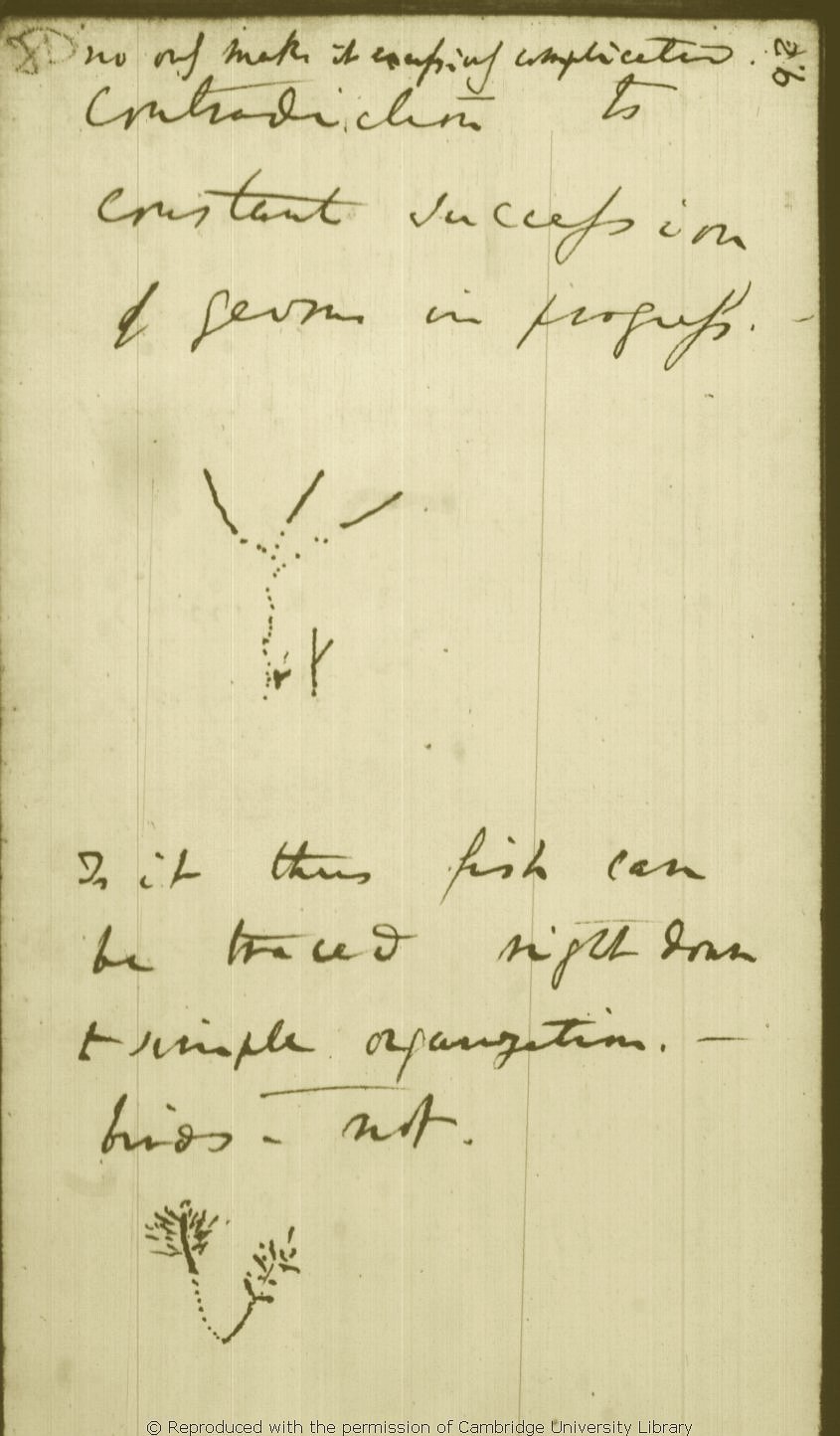

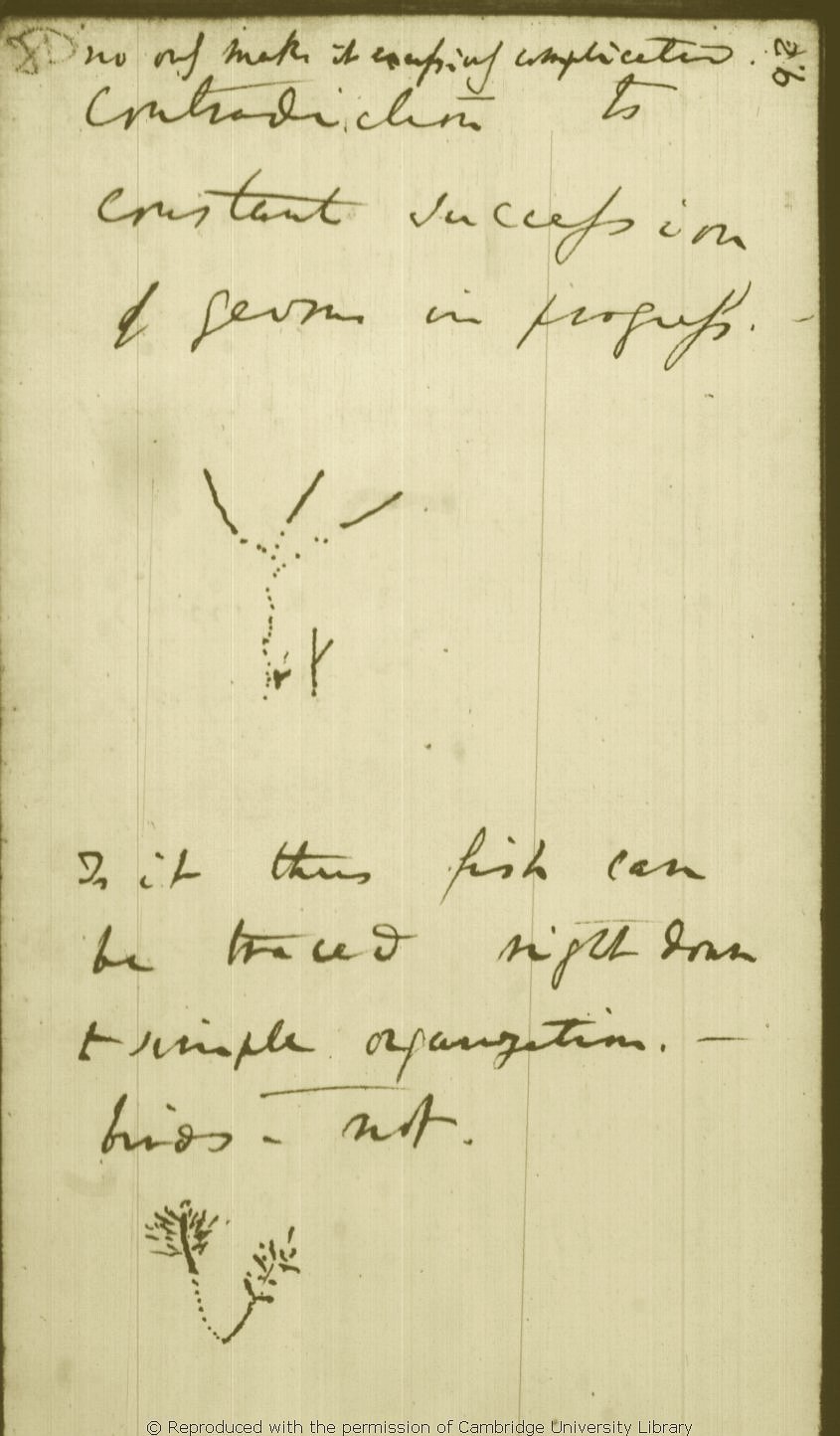

[page] 26

contradiction to constant succession of germs in progress

no only makes it excessively complicated.

[sketch]

Is it thus fish can be traced right down to simple organization. — birds — not?

[sketch]

[page] 27

We may fancy according to shortness of life of species that in perfection, the bottom of branches deaden,

so that in Mammalia, birds, it would only appear like circles, &

insects amongst articulata. — but in lower classes perhaps a more

linear arrangement. —

[page] 28

¿

How is it that there come aberant species in each genus (with well

characterized parts belonging to each) approaching another.

Petrels have divided themselves into many species, so have the Awks, there is particular circumstances to which

is it an index of the point whence, two favourable points of organization commenced branching. —

[page] 29

As

all the species of some genera have died, have they all one determinate

life dependent on genus, that genus upon another, whole class would die

out, therefore not. —

Monad has not definite existence. —

There does appear some connection shortness of existence in perfect species from many therefore changes and base of branches being dead from which they bifurcated. —

[page] 30

Type of Eocene with respect to Mioce of Europe?

Loudon. Journal. of Nat History. —

July 1837. Eyton of Hybrids propagating freely

In Isld

neighbouring continent where some species have passed over, & where

other species have come "air" of that place. Will it be said, those

have been there created there; -

[page] 31

Are not all our British Shrews diff: species from the continent

Look over. Bell & L. Jenyns.

Falkland rabbit may perhaps be instance of domesticated animals having

effected. a change whi the Fr. naturalists thought was species

Ascensi Study Lesson Voyage of Coquille. —

[page] 32

Dr. Smith says he is certain that when White men & Hottentots or Negros cross at C. of Good Hope

the children cannot be made intermediate. The first children partake

more of the mother, the later ones of the father. Is not this owing to

each copulation producing its effect; as when bitches puppies are less

purely bred owing to first

having once born mongrels. he has thus seen the black blood come out

from the grandfather (when the mother was nearly quite white) in the

two first children

How is this in West Indies?

Humboldt. New Spain: -

[page] 33

Dr.

Smith always urges the distinct locality or Metropolis of every

species: believes in repugnance in crossing of species in wild state. —

No doubt C.D. wild men do not cross readily, distinctness of

tribes in T. del Fuego. the existence of whiter tribes in centre of S.

America shows this. — If

Is there a tendency in plant's hybrids to go back? — If so, men &

plants together would establish Law, = as above stated. — No one can

doubt that less trifling differences are blended by

[page] 34

by

intermarriages; then the black & white is so far gone, that the

species (for species they certainly are according to all common

language) will keep to their type: in animals so far removed with

instinct in lieu of reason, there would probably be repugnance, &

art required to make marriage. — As Dr. Smith remarked, man & wild animals in this respect are differently circumstanced.

[page] 35

¿ Is the shortness of life of species in certain orders connected with gaps in the series of connections?

If starting from same epoch certainly

The absolute end of certain forms from considering S. America (independent of external causes) does appear very probable: —

Mem: Horse, Llama, &c., &c. —

If we suppose

grant similarity of animals in one country owing to springing from one

branch, and the monucle has definite life, then all die at one period

which is not the case, ∴ monucule not definite life.

[page] 36

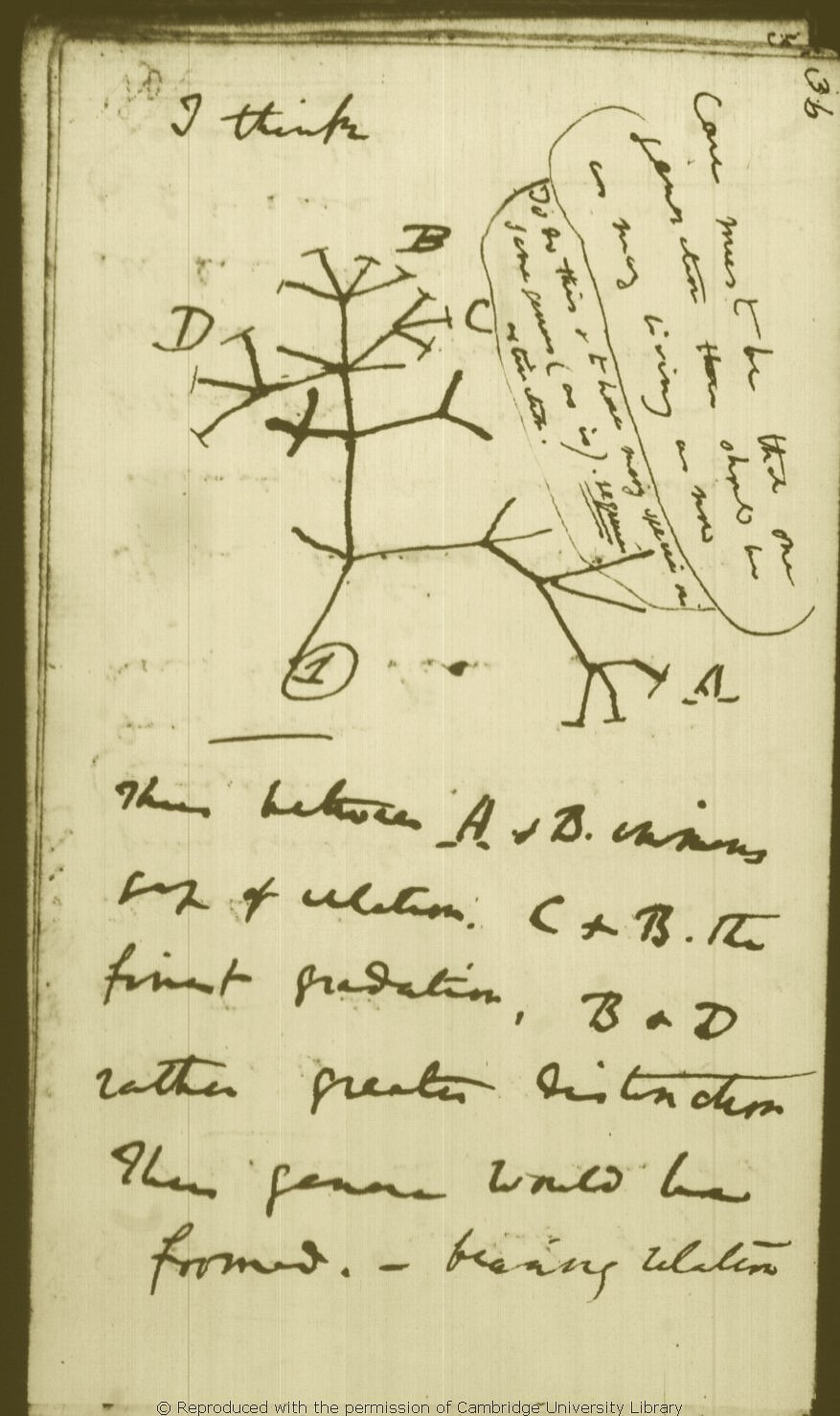

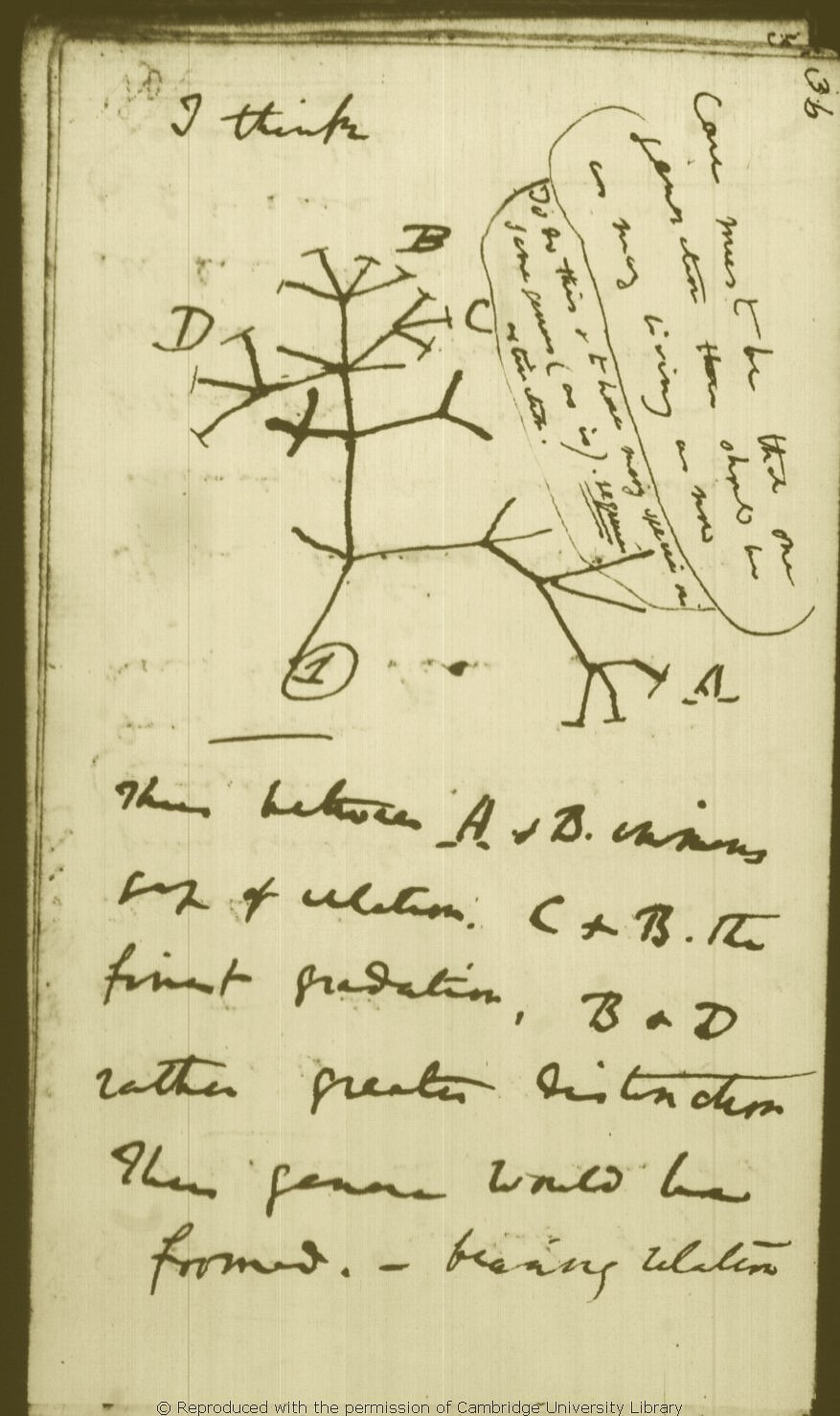

I think

[sketch]

Case must be that one generation then should be as many living as now.

To do this and to have many species in same genus (as is) requires

extinction.

Thus between A & B immense gap of relation. C & B the finest

gradation, B & D rather greater distinction. Thus genera would be

formed. — bearing relation

[page] 37

to ancient types. — with several extinct forms

for if each species an ancient (1) is capable of making 13 recent

forms, twelve of the contemporarys must have left no offspring at all,

so as to keep number of species constant. —

With respect to extinction we can easy see that variety of ostrich,

Petise may not be well adapted, and thus perish out, or on other hand

like Orpheus being favourable

[page] 38

many might be produced. — This requires principle that the permanent varieties produced by inter

confined breeding & changing circumstances are continued &

produced according to the adaptation of such circumstances, &

therefore that death of species is a consequence (contrary to what

would appear from America)

[page] 39

of non-adaptation of circumstances. —

Vide two, pages back.

Diagram

Courtesy of Darwin Online © University of Cambridge.

Transcribed by Kees Rookmaaker 1-2.2007 based on Barrett, P. H. ed.

1960. A transcription of Darwin's first notebook [B] on 'Transmutation

of species'. Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard 122: [245]-296, for 1959-1960 (April). [Text] and corrected against the microfilm. Deletions, punctuation and page numbers were added. Edited by John van Wyhe. RN1

See the fully annotated transcription of this notebook by David Kohn in Barrett, Paul H., Gautrey, Peter J., Herbert, Sandra, Kohn, David, Smith, Sydney eds. 1987. Charles Darwin's notebooks, 1836-1844 : Geology, transmutation of species, metaphysical enquiries. British Museum (Natural History); Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Reproduced with the permission of Wilma M. Barrett, the Syndics of Cambridge University Library and William Huxley Darwin.

|